As a photographer, techie, movie buff, and (infrequently) gamer, I am a data-hog. As much as I love SSD’s, to date, they have been too cost–prohibitive to justify for many of my uses. With 32TB of spinning rust on my desk alone, I simply couldn’t justify it — until recently. Over the lock-down periods I have been sorting files out, ditching many media files, moving others to cloud platforms, gradually reducing my data footprint. In addition, SSD prices have become far more reasonable in the recent term – not cheap, but reasonable.

I am well aware though, that not all SSD’s are made alike. Some with TLC flash, others with QLC…. some with onboard RAM, some that are DRAM-less. A lot of research must be done to find a suitable SSD model to meet your needs. In addition, in recent times, various unscrupulous tactics have emerged by the SSD manufactures, in particular, part substitution.

Normally, part substitution is an invisible and fairly common practice, where some of the components on a piece of electronics may be substituted over time. Usually this is done due to deals made by manufactures, where a better deal on a part is negotiated from another supplier. The most important point is that these substitutions are normally equivalent – like for like swaps, with equivalent performance, so that the end product does not end up having different performance specifications. For example, a swap from 64-layer to 96-layer flash memory does not affect some drives as much.

Recently, a number of SSD manufacturers (WD Blue SN550, Crucial P2, Kingston NV1) have been caught substituting TLC flash memory on their products for QLC flash memory. Unfortunately this is not an equivalent swap, but rather is a switcheroo, as QLC flash memory has far, far lower performance in data write speeds, as well as a much lower endurance (data re-write lifespan). The drop in performance is so large, that WD has even gone as far to offer QLC SN550 SSD buyers a swap for those who are unhappy with the lower performance.

Other manufactures have also got into hot water for swapping out other parts, like controller chips, or removing RAM chips, which also affects the performance, but to a far lesser extent.

PNY Enters the SSD bait-and-switch game

In 2020, PNY made some headlines for quietly reducing the advertised performance of some of their SSD models. In particular, the CS3030, a mid range model, had the endurance of the drive reduced by 80%. A swap from TLC to QLC was suspected, but to date I have found no confirmations that this was the case.

Recently, I found a cracking deal on a PNY CS1030 2TB NVME SSD, for just $200 AUD!I was looking for a data-only drive, not a boot drive, so I was looking in the low to mid tier for a model with good value $-to-GB as a higher priority. Released in Feb 11th 2021, this is budget DRAM-less drive, and it was advertised with read/write speeds of 2100MB/s and 1900MB/s respectively. A year later, and still very few reviews exist for the PNY CS1030 – the only one I found was from ServeTheHome, from June 2021. In that article it was explicitly said:

The [flash] NAND on the CS1030 appears to come from Yangtze Memory Technologies Co (YMTC) and is TLC.

and…

Repeating a gripe from the PNY CS2130 review, the PNY CS1030 line of drives suffers the same lack of transparency with regards to the specs on the drive.

The PNY CS1030 is not advertised with a specific MBTF endurance rating. Strange, but perhaps partially forgivable for a low-end SSD, one that is not intended for business-grade use. However, the firm statement that this drive was TLC, and the very respectable performance numbers seen in that single review gave the impression that this drive would be quite serviceable for my needs… so I pulled the trigger and ordered one.

After receiving the drive, initial benchmarks appeared as expected. However, after some large extended write tests major performance issues started to appear – write speeds initially rapidly dropping to under 400MB/s, and then going lower still. As with most QLC drives, pseudo-SLC buffering techniques can be used to temporarily hide the true poor performance that QLC offers. However, when doing large writes this buffer can be exceeded, and as a result the performance then cratered, with write speeds as low as 35MB/s.

Simply terrible write performance from the PNY CS1030 with QLC – benchmarked with CrystalDiskMark 8 immediately after exceeding the pseudo-SLC write cache.

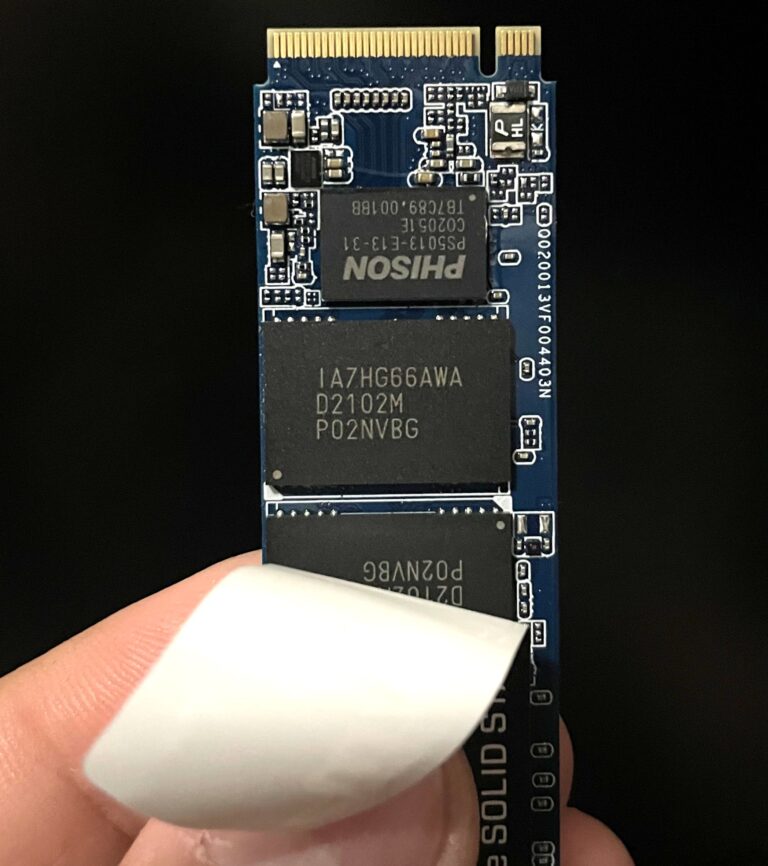

With such poor performance I started to wonder… had PNY pulled a switcheroo as well? I removed the SSD from my computer and inspected it (image below). This revealed the true nature of the PNY CS1030… it was a QLC drive! The scumbags!

TL;DR – The PNY CS1030 is a QLC drive.

PNY CS1030 2TB QLC Specifications

- Flash chip markings: IA7HG66AWA D2102M P02NVBG (96-Layer 3D QLC NAND flash from Micron)

- Controller chip markings: Phison PS5013-E13-31 CO2051E TB7C89.001BB

- Firmware: CS103700

I found your blog while researching problems with my PNY CS1030 NVME drive. Read speeds on occupied sections of the SSD dropped to < 600MB/s! 'Empty' portions had a fast read speed, but what's the benefit of that? Large writes bog down Linux. (Yes, I had trim/discards enabled.)

Lifting the label reveals the Phison PS5013 controller… Have not yet tried firmware update tool. (Windows only)

And, copying many small files may also slow the drive file transfer rates further! Overall I do not recommend this drive except for cheap bulk storage.

Am a bit confused, but agree on the TBW. There is no good excuse not to mention TBW other than sloppiness or intent to hide it.

On the memory side, you mention that QLC flash memory has “far, far lower performance in data write speeds, as well as a much lower endurance (data re-write lifespan). ” But, QLC NAND flash memory stores four bits of data per cell, while TLC only stores three bits. This higher density means that QLCs stores more data in the same physical space.

Did I misstand your post or mix things up?

john

You’re right that QLC store more data in the same “space” — but the actual physics that dictate how this process works mean that it takes a longer time to read each flash cell. This is why QLC drives tend to be cheaper (less silicon area required per drive, higher storage density), but slower (longer time to read and write/verify each cell). Additionally, the number of write cycles per cell also depends on the bits per cell.

The original SLC flash memory used 1 bit per cell, MLC had 2, and TLC has 3. Each time we increased the cell density, the max speed and durability of the flash cells decreased.

There are some great articles elsewhere that go into more detail:

– Techtarget – QLC-vs-TLC-NAND-Which-is-best

– Synology – TLC vs QLC SSDs